Frequently asked questions

Adelaide's coastline is one connected system but some of our beaches can experience significant erosion.

Parts of the southern and central beaches along Adelaide’s metropolitan coastline can experience significant sand loss and erosion of sand dunes, particularly over the winter months.

The sand along Adelaide’s coast is naturally moved northward by the wind and waves. This causes sand to build up on our northern beaches, and sand loss and erosion along parts of our central and southern beaches. The State Government manages the metropolitan coastline to protect the foreshore and coastal development from storms while allowing the community to enjoy sandy beaches.

Beach operations to move sand have occurred across the metropolitan beach system for nearly 50 years.

Sand is a finite resource - it needs to be shared equitably along our coastline so we can all enjoy sandy beaches.

- West Beach has had serious and ongoing erosion for decades. Beach levels at West Beach and Henley Beach South were at their lowest in more recent years than at any other time since records began. Further north the beaches are generally in better condition as the sand lost from southern beaches drifts north replenishing beaches over the warmer and calmer months.

- For many decades sand has accumulated on Adelaide’s northern beaches and continues to do so leading to wider beaches and dunes from around the Semaphore jetty northwards.

- The beaches in the southern part of the coast (from Glenelg to Kingston Park) are generally stable. These beaches have been managed by an underground pipeline and sand pumping system since 2013.

What happens if nothing is done to address erosion at West Beach?

If the beach and dunes aren’t replenished at West Beach, the erosion problem will get worse and progressively move northward impacting other beaches. Coastal infrastructure, roads, facilities and beach amenity would then be affected and under threat from storms.

On our northern beaches some dunes will continue to grow in width and height. Sand will continue to build-up on these beaches, with the water becoming very shallow to swim or fish in, and jetties could eventually become land-locked.

What research has been undertaken?

In 2017, a coastal processes modelling study was commissioned by the Department for Environment and Water, the Coast Protection Board, the City of Charles Sturt and West Beach Parks to better understand the coastal processes at West Beach and to examine alternative management options. This was needed because of the ongoing loss of sand each year at West Beach.

External consultants and international coastal experts DHI completed a report in 2018.

- The research undertaken by DHI showed that the sand loss at West Beach (the section of coastline running north from the West Beach boat harbor at West Beach Parks to the Torrens Outlet) is significant, and greater than previously estimated.

- The report made it clear that even if management activities were maintained, erosion will continue around West Beach and Henley Beach South, and progressively move north.

- The report tested out three alternative scenarios for managing the beach and dune erosion at West Beach, with their results modelled. All three options involve beach replenishment and varied by bringing in differing amounts of sand over different timescales.

During the course of the study, the scope was amended to expand the analysis of beach profiles along the entire system from Kingston Park to Largs Bay, to enable a better understanding of the influence of management of adjacent beaches on West Beach and vice versa. This expanded analysis also provided insight into the management of the entire Adelaide beach system.

Why aren't structures like groynes built to try to reduce the natural drift of sand northward? What other alternatives have been looked at?

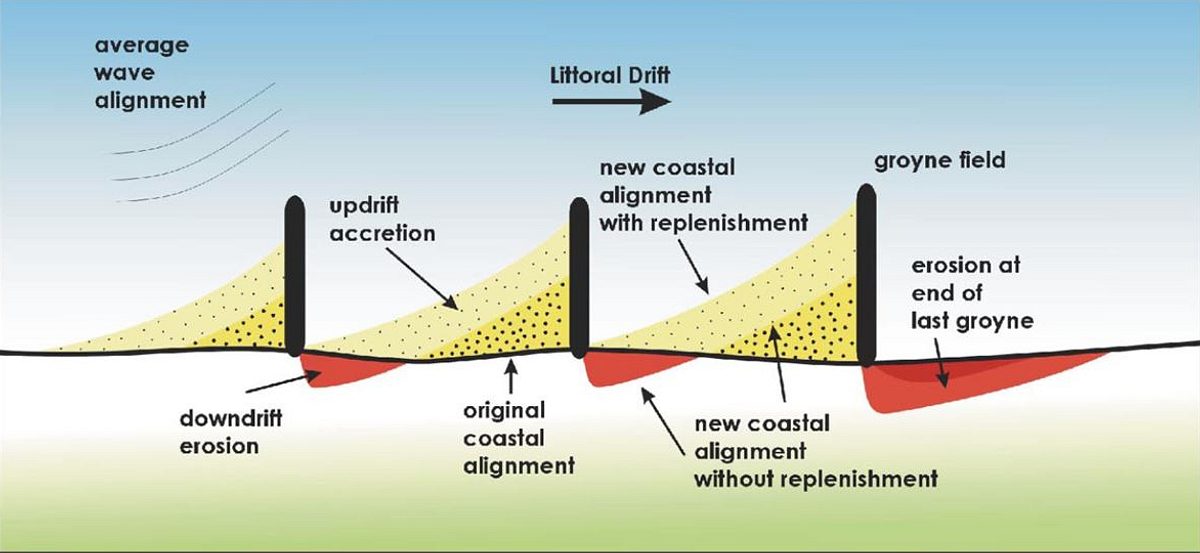

Fixed structures are very expensive to build and still require large volumes of nourishment sand to be added to “pre-fill” the area following construction. This pre-filling with sand is essential otherwise the coast to the north of each structure would erode. Depending on the size of the structure, often beaches to the north of the structure will require on-going maintenance such as beach replenishment to address this ‘down-drift-erosion effect.

In addition, the experience with existing structures on the Adelaide coast and elsewhere in South Australia is that they trap large quantities of beach-cast seagrass or algae (seaweed) which can have an impact on the usability of the beaches and increase management costs.

When factoring in these aspects, the sustainable approach to managing our beaches involves recycling sand from areas where sand builds up to areas of loss. This means the protection of Adelaide’s beaches can be achieved without negative impacts from structures, which would interrupt amenity and recreational use along our sandy beaches.

Options involving the construction of hard engineering structures to re-orientate the West Beach shoreline were considered by DHI and included offshore breakwaters and headland control structures. A range of risks and disadvantages were identified with these options: they are costly to install, require large quantities of sand, trap seagrass wrack, can be a safety hazard, are visually unappealing, interrupt recreational beach use and can cause the coast on the northern side of the structure to become starved of sand.

Case study - Dune restoration at Seacliff beach

During the 1980s and 1990s, the Seacliff and Brighton coast was suffering from severe erosion that threatened the foreshore. To address this, a large scale beach replenishment was undertaken.

During the 1990s over 1 million cubic metres of sand was dredged from sand deposits offshore of Port Stanvac and delivered to that section of the coast, which formed and stabilised the dunes and in turn helped to stabilise the beach.

The operation of the Glenelg to Kingston Park sand recycling pipeline has maintained sand volumes and kept this part of the coastline stable since 2013.

What is being done to help beaches outside of Adelaide?

Local councils play a critical role in protecting regional assets from coastal hazards and maintaining coastal areas for all South Australians and tourists.

Coast Protection grants are available for projects that help to sustain, restore and protect our precious coastal resources via two annual grant programs. Learn more.